1880 to 1913

© Copyright: J Knight & Horsham District Council 2006

Cover and format designed by Horsham Museum and Horsham District Council

J Knight has asserted his right under the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author

of this work

British ISBN 978-190248441-9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

PREFACE

An apology from the author – “It is impossible to write ancient history because we do not have enough sources, and impossible to write modern history because we have far too many”. So wrote Charles Peguy in Clio (1909-12), whilst the length of time taken to get out volume three: two years covering thirty, compared with two years covering the span of Horsham’s history up to 1880, can also be answered in a quote by Thomas Jefferson in 1817 when he wrote to a Dr Smart: “To write history requires a whole life of observation, of inquiry, of labour and correction. Its materials are not to be found among the ruins of a decayed memory”[1].

I could leave it at that and let you, the reader, come to your own conclusions. However, one of the great frustrations faced by any historian has is having to second guess. So, to save the frustration, please read this introduction which explains why volume three took two years, why I have altered what I proposed to do in volume 1 and where I plan to take the work forward from here.

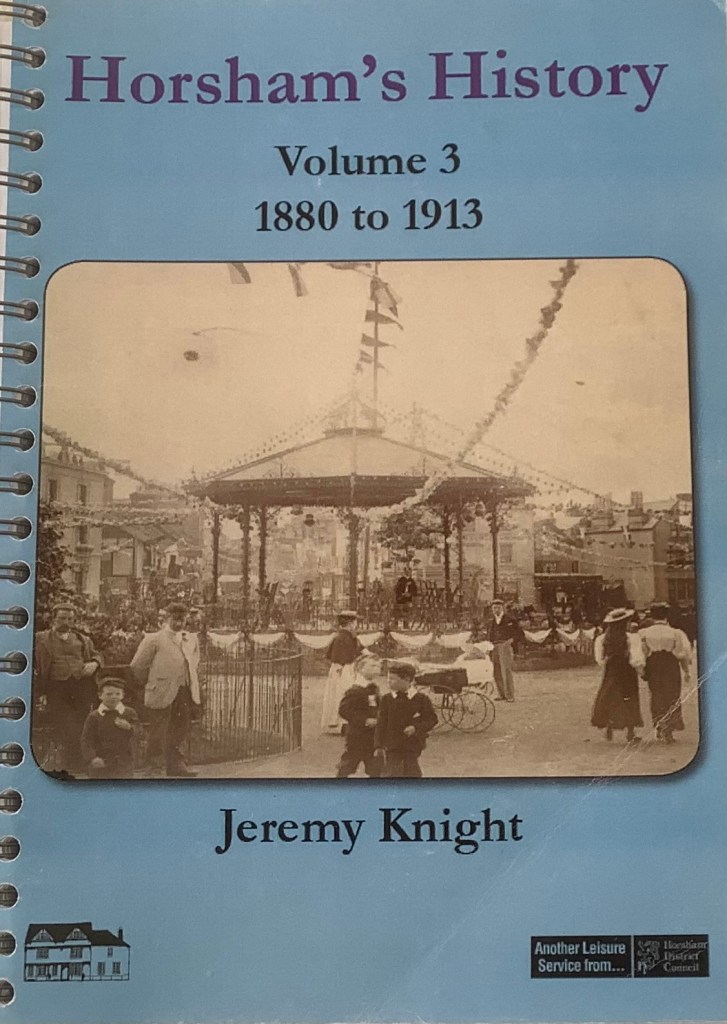

I started this book in December 2006, a month after finishing the first two volumes. I had intended that book to complete the Horsham story up to 2000. However, within a month it became very clear that, whilst entirely possible, the amount of material available and the story that the untapped resources revealed made it a great lost opportunity. Lytton Strachey argued that “Ignorance is the first requisite of the historian – ignorance, which simplifies and clarifies, which selects and omits…” I could so easily have deliberately remained ignorant of the material housed in Horsham Museum archives, on the microfilms of the local newspaper, of the accounts in the Parish Magazine, so that these thirty years would have been covered in one chapter. I could have just written about the rebuilding of the Town Hall in 1888, the building of the bandstand in 1892, the Cottage Hospital in the same year and the creation of Collyer’s new home in 1893, whilst the decade leading up to the First World War was the lull before the storm.

Yet I chose to explore the period in greater detail. Why? The period isn’t my preferred area of research: that is, the 18th century, so before tackling the period I read, not cover to cover, but in some depth, New Oxford History of England; A New England?: Peace and war 1886-1918 by G. R. Searle. It was an eye-opener, for whenever I picked up a document, or read a newspaper account, I could see parallels in Horsham. I read in January 2007 with great amusement the great controversy over caning children, a Horsham controversy that led to editorials in The Teacher. I would not have known this if the museum hadn’t been given a scrapbook by a descendent of one of the Local School Board members. Yet what put the debate in perspective was that the controversy occurred at the same time the National Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children was formed. What was in reality a minor debate had echoes on the national stage and opened up a view of how some in Horsham regarded children and their status, as well as their legal rights. This so obviously could be a stepping-stone to a far greater study, yet I had to draw the line and not pursue it any further. It was, however, a realization that so much of what I looked at could have echoes elsewhere that led me to develop the chapters more fully.

All previous historians of Horsham have to a large extent ignored Horsham post-1880, a point made in the previous volumes. However, there is a wealth of material out there that can be explored. To encourage this I also decided to cover things in greater detail as well as offer longer extracts from original sources. For example, I was looking at a Directory of 1906 when the phone rang. It occurred to me that telephones must have come into use around this time, and the advert for a trader had a one-digit phone number, but another trader had another type of number, so after spending a couple of hours looking at the directories and then the internet I had a narrative that explained how telecommunications came to Horsham; a story that hadn’t been told before. No doubt future historians will create a different narrative, but at least there is now an “in the beginning” phase. And so it goes on.

So you will see how one month soon ran in to two; then six, and finally twelve. In November 2007 I started working on Horsham during World War One. I wanted to get the research done so I could mount an exhibition in January 2008. In February I went to Hong Kong, using the first few days there to recover from jet lag and to read through what I had written. I soon realized that whilst I could get 1914-18 into the third volume, it would have made the book too thick and would have taken a lot of time to fine-tune the story. I had re- read the chapters for 1880-1913 and decided that although they are long, the story they told was interesting to me. So on my return I decided to use volume three to cover 1880-1913, and would aim to get the book out by June.

Then by chance I picked up two weighty tomes in Colin Pages in Brighton; two seriously academic works whose titles would or could put most people to sleep: one on the history of taxation, the other on estates and marriage. But browsing through them in the shop basement I could see echoes of Horsham’s story – a whole new chapter on local government finance was opening up – Horsham’s arguments were mirroring national debates. So, a delay and a re-think and new additions.

In the meantime Julie Mitchell had kindly proofread the text and tidied it up etc.; however, she strongly recommended, after comments made by the editor of Horsham Society Newsletter that the text should be proofread by someone else. Fortunately for me, Jason Semmens, the Assistant Curator, agreed to do so, again in his spare time, which was fully-stretched with his own research and publications on Cornish witchcraft/folklore. This rightly caused more delay in the publication of the work, but the time enabled me to undertake fine-tuning of the research and it was now that I made probably the most significant discovery of this volume. I had taken as “gospel” the comments made by Dorothea Hurst about the Town Hall and never checked them (neither had previous historians), but I decided to read the newspaper accounts, the original documents held by Horsham District Council and the letters file held at West Sussex Record Office concerning the rebuilding of Horsham Town Hall. It was one of the iconic events of the Victorian period: Horsham Town Hall was rebuilt in 1888; Dorothea Hurst, who lived through the period and published her history only a year later, says the Town Hall was pulled down and rebuilt. But the actual records show that it wasn’t; it was refurbished and some structural work carried out, but not a rebuild. This would tie in with other evidence – no plaque marking the rebuild (one was put on the fountain only 10 years later), and no photographs of the civic opening of the Town Hall, for there wasn’t one. A Town Hall, the monument to civic pride, would have had a grand ceremony; look at the bandstand four years later; but the Town Hall had nothing.

So the delay in publication enabled further revelatory research to be undertaken. I hope and trust other people will explore the period further and agree or disagree with the account given here. I have tried to give the sources of the material used, so you will have a guide. This is the first stage in reclaiming Horsham’s forgotten history, in creating a narrative different from decayed memories.

And just to point out how it will be possible for future historians to add to this account, the week before writing this Preface, Sue Djabri emailed me the following note:

Dear Jeremy,

I have now got to the part of the Denne Road Cemetery burial records dealing with the period of the measles epidemic in 1886 and have produced a few facts and figures which you might care to add to your text, maybe as footnotes, as they really point up the severity of the outbreak. Pam said that you were away all week, so I am sending this to both your e-mail addresses, in case you are doing final work on Volume 3 at home!

63 children were buried in Denne Road cemetery in the first quarter of 1886 (out of a total of 88 burials during that period). This was a huge increase compared with the previous quarter, when there were nine child burials out of a total of 33, and the following quarter when there were 13 child burials out of a total of 31 – these figures were normally much the same throughout the year. Seven children and four adults died at the Horsham Union workhouse in Crawley Road during the first quarter of 1886, as opposed to a total of four and two deaths in the previous and following quarters.

The most tragic case was when three children from one family were buried on one day – 19 February 1886 – when the epidemic was at its height: Robert J. Oakes of Queen Street lost his two daughters, aged 5 months and 4, and his son aged 2. The youngest child, Nellie Oakes, was privately baptised on 11 February, as were several other children during the epidemic, presumably because they were so ill that it was not possible to take them to church. Two of the other children privately baptised, Emma Palmer and Annie Reynolds, also died a few days later.

The children were mainly buried in section E of the cemetery – possibly in mass graves as there are clusters of consecutive grave numbers – with a few individual burials in sections C, D and L. From the Horsham Parish burial records (as transcribed by the Parish Register Transcription Society), which give the place of some of these deaths, it would seem that Queen Street, New Street, Horace Street and Park Terrace, on the east side of the town, were the streets worst affected by the epidemic. This is in line with the record of aid given, in the Parish Magazine, which was concentrated on the eastern part of the town.

Hope that this may be useful,

And for those that want to know, the next volume will cover The War Years 1914-1945; volume 5 – Post War Horsham – up to 2000. There will be a detailed index for this volume published later.

Acknowledgments

This is probably the one area that gives people the most pleasure writing, but often gives little evidence to the reader of the actual level of contribution to the work in hand. Owing to the vagaries of technology, and after having many people try the Word program which continues to produce American English, which is fine if I were producing a history of Horsham USA for the American market, therefore I would like to thank Julie Mitchell for the first proofreading of the text and Jason Semmens for a second proofreading. Both of them have performed a task beyond the call, and those in the know, know all too well why it is more than just ‘different English’. I would like to thank Bill Mathews for scanning the images. Brenda Brewer for transferring and sorting out the document and images so it can be published. Horsham District Council’s Reprographic Department for producing the book. Sue Djabri and Jason for being an ear to some of the debates aired here. Sue also helped out with some supplementary information based on her research into family history and for her book Images of England Horsham.

I would also like to thank museum staff for the encouragement to continue this work, as well as members of the public who, in asking when the next volume would be out, gave unknowing support.

In the 17th century cats were referred to as “an idle mans play thing” – both Parker and Coco; particularly Parker, tried their best to stop this book coming out, but they failed, though only just – cats, I have discovered, cannot see why a laptop should compete for the lap. And when not working on a lap I had the opportunity to work on and I would like to thank Adrian for providing a large table and floor space which gave me the opportunity to spread out when not working on my lap.

A brief note about money

Throughout the book sums of money are identified. Those born before 1976 will be familiar with, though by now may have forgotten, pre-decimalised money. The following note is by way of explanation:

Before 1971 money in Britain was based on pounds, shillings and pence, which itself had its origins in the Anglo-Saxon period. There were 20 shillings to the pound, 12 pennies to a shilling. The coins were a crown (5 shillings), half crown (2.5 shillings), shilling, sixpence (.5 shilling), threepence (three pennies), penny, halfpenny and a farthing, (one quarter of a penny).

Napoleon in the 1790s/1800 instituted monetary reform in Europe based on a hundred rather than twelve, but it would be another 170/180 years before Britain followed suit!

At the time of the changeover in 1971, one old penny was equivalent to just less than half a new penny; a shilling was equivalent to 5p.

Some coins ceased to be legal tender before the changeover, so the farthing (a quarter of a penny), which was introduced in 1613, ceased to be legal tender in 1960. The old halfpenny was removed in 1969 and a new halfpenny was introduced to replace the old penny, though that now has ceased to exist. As things became more expensive the need for very small units of money died out. (It could be argued that rather than things becoming more expensive the actual value of the money was debased so it could buy less – either way the effect was the same: you could no longer buy items for the smaller denominations of money.

NOTE: I have not produced contemporary values for the sums identified, as:

- they will date

- the Bank of England produces current conversion tables regularly updated to convert values into modern-day equivalents

- by giving a modern-day equivalent it gives it a value that is out of context.

If you do want to know the current-day value there are a number of websites that tell you, including one run by the Bank of England.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

THE NAKED CHRONOLOGY

| 1880 | A writer considers the town with its trees, wide streets and numerous open spaces as having a continental look. A nonconformist Sunday school room built of red brick and seating 300 opened this year. Later, it would become Albion Hall in Albion Road. In Roffey a working men’s club is opened under the management of the vicar, which has a hall, a library and a reading room. A roller-skating rink opened around this time in Brighton Road, which by 1912 had become the Olympia skating rink. |

| 1881 | Horsham’s population reaches 9,556 according to the census. |

| 1882 | The Horsham Liberal Club in Albion Terrace opened with reading, smoking, recreation and refreshment rooms. The Horsham Times and West Sussex Courier with its independent views of politics and church, published first in Crawley and then Lewes, flourishes till 1941. The poultry market moved to the Swan Inn and then to the Black Horse. The following year the local board of health acquired the markets, leasing the tolls in 1884 for £5. |

| 1885 | Henry Padwick, who bought Stammerham from the Shelleys in the 1870s, sold it to the Aylesbury Dairy Co. In 1892 the Company went broke and sold the 1,300 acres to Christ’s Hospital School. |

| 1886 | Hawthorne House, which stood adjacent to the Manor House, was demolished. The following year, Tanbridge House, built in a Jacobean style for the railway contractor Thomas Oliver, who included two 16th century fireplaces from its predecessors that stood nearby. The Horsham Club in Carfax opened; within two years it had around 170 members. |

| 1887 | Monday and Wednesday markets for poultry and corn were held respectively, with cattle being sold on alternate Wednesdays. Later, selling by auction was introduced. The local board abolished the July Fair. It had its offices in the Town Hall. |

| 1888 | The Parish Room was built with a library in Causeway. The Horsham Advertiser, first published in 1871, changed its name to West Sussex Times, boasting that it was the paper of the new county. It was pro-Tory and Church. Five years later, after two further title changes, it became The West Sussex County Times. Springfield Park House had become a school, Horsham College, in 1904; Gerald Blunt opened its successor. Local board of health bought the Town Hall and repaired it. |

| 1889 | The July Fair was reinstated in Bishopric under the local board. Then held in Jew’s Meadow |

Horsham 1880-1890

HORSHAM CHANGES

On 4 November 1880 Horsham’s last burgage-holder, Pilfold Medwin,[1]died. Pilfold was the youngest son of Thomas Charles Medwin, and brother of Thomas Medwin, the biographer of Byron and Shelley. Only months before, he cast his vote as a burgess, insisting on his right to do so, even though he could have voted through the increase in franchise caused by electoral reform that saw 1109 votes cast at that election. That election had been between James Clifton Brown and Sir Henry Fletcher.[2] (The Liberals were still carrying the blue colour; the Conservatives, pink.) Meetings were held at different public venues including the newly-built skating rink[3], just east of the iron bridge, as the electorate was so large and the party management system too weak to fund individual door to door canvassing en masse. However, problems could arise at such meetings (unlike hustings where both candidates were present), for rumours would spread, and there was no control of the message. For example, it was rumoured that Brown said “The working-man was nowadays too extravagant in his tastes; he wanted ham and eggs for breakfast”. A damning comment if genuinely made by the Liberal candidate. Polling took place on 1 April 1880 and Sir Henry won the seat from Brown. Even though there was a great deal of drinking going on and Mr Bull, the Under Sheriff, had arrived in the town to make arrangements for a petition for corruption, no petition was forthcoming, for Brown was, according to Albery, too radical even for his own party and Sir Henry too popular[4]. This was a rare uncontested election. The nation as a whole, though, voted in a Liberal Government and so the writing was on the wall for Horsham to remain as a Parliamentary seat.

The death of the last burgage holder (who because of his status retained the right to vote in elections, a remnant of the pre-1832 Reform Act), was also a portent for the coming decade, for the next ten years or so would see the last vestiges of medieval and Georgian Horsham broken and the emergence of a new Horsham, a Horsham for the modern age, though ironically it was a modern age that wished for the veneer of its past.

In this decade the old political certainties of Whig and Tory would be changed into the two-party politics of Liberal and Conservative; the old Market Hall would be pulled down and rebuilt as a Town Hall, the fairs would be stopped by an Act of the Home Secretary only to be re-established with new rules and regulations; the management of the county services through Quarter Sessions would be transformed through the creation of a County Council; Horsham itself would lose its own MP as Horsham became absorbed into a larger political area. As for Collyer’s, its days were numbered, both physically and constitutionally, and it would re-emerge phoenix-like in the early years of the next decade as a Grammar School worthy of its origins, after a century of slumber. The next decade was momentous for Horsham.

With the formation of a Local Board in the previous decade, Horsham had a group of people who saw the virtue of Local Government. But what was Horsham like at this time? G. F. Chambers, in Tourists’ Guide to Sussex, described Horsham as having a continental aspect, with its trees and wide streets, with the Carfax being singled out as an “oasis in the business quarter of the town”[5]. Following on from the Franco-Prussian war and the resultant turmoil in Paris mentioned in the previous chapter (see Vol. 2), Paris underwent major redevelopment with the creation of wide boulevards which would, it was thought, stop the erection of barricades. These wide streets were obviously in the mind of the writer though Horsham, even with its rebuilding, could never really be described as Continental[6].

It does, however, show that the Local Board’s investment in paving was paying off in terms of creating a modern image of Horsham. The Local Board was primarily set up to deal with sewage and clean water, but in 1878 it had also taken over the interests of the parish highways board which included lighting and paving. In 1879 the sewage works had been completed at a cost overrun of nearly £6,000 (est £7,590, actual £13,560), they had bought out the Waterworks at £7,000 and now, on 9 July1880, they had an estimate to pave the District[7]. The report produced by the Surveyor on behalf of the Horsham Local Board Works and Drainage Committee sets out the recommendations and the cost to carry them out:

1. “That with accord to the question of paving. Asphalt be the material used in the outlying parts of the District

2. That New Street, Barrington Road, Station Road, Bedford Road, Arthur Road, Rushams Road, Percy Road, Trafalgar Road, and Saint Leonards Road be paved on one side with asphalt and kerbed

3. That a 4 feet 6 inch pavement be laid from the Skating Rink to corner of New Street, and a 3 feet 6 inch pavement in Park Street

4 That the money required to carry out the proposed works of paving be borrowed and that the Surveyor be instructed to prepare Estimates of the possible amount required”

This he did, and itemised, identifying that the paving wasn’t to be in Horsham stone as one might have thought, but Victoria stone. The estimate also shows that New Street and Trafalgar Road would have five feet wide asphalt paving; the others as specified, 5 feet 6inches. The total estimated cost was £1209.8.9d.[8]

Unfortunately, we don’t know if the plan went ahead, but as the Local Board was not averse to borrowing money and saw it as imperative to make up for lost time, it probably did.

The apparent willingness of the Local Board to borrow may seem at odds with the perceived notion of Victorian prudence of living within one’s means; and the stigma of debt was genuine, for debt could, and did, mean the workhouse. However, in reality such sermons were preached to the poor rather than the middle or landed classes, who were able, as the ledgers of William Albery’s saddlers business show, to have credit for one or two years with no interest charged. The people who ran Horsham’s Local Board were the same people receiving credit in the trader’s shop. In addition they could argue, as did the Labour Government in the late 1990s, that they were borrowing to invest in the future, not to cover running costs – investing in infrastructure; not wages. As such it was a well-judged policy, for the town needed major structural investment if it was to become comparable with other leading towns of Sussex, the towns of the coast; not the countryside. Economic power had moved in the Victorian period to the coast away from the countryside as agriculture declined in importance on the national scene, but Horsham had the ability through its superb rail network to become the capital of Sussex, the county town.

This forward-thinking and, one might argue, dynamic approach: no longer being passive receptors of events taking place around them, but physically shaping the future of Horsham, can also be seen in the mental culture of the town. As will be seen below, Horsham was indulging in some serious debates and working through issues for itself, which may be seen as surprising.

The surprise comes from perceived ideas about Victorian Horsham; ideas encouraged by two key elements: the idealisation in the late Victorian times of the countryside as played out in the literature, which for convenience will be termed “Back to the Land”[9], that will be explored below, and the Reminiscences of Henry Burstow. The latter book, which has been quoted from in the previous chapters, is the semi-autobiography of a cobbler. It was used by William Albery and others as the authentic voice of Horsham but, as will be shown later, it very much fitted in with the notions of a Back to the Land movement. If Burstow knew of the discussions taking place within the town, he filtered them out; thus providing Albery with the self-confirming narrative he wanted to hear. The other option, and probably just as likely, was that Burstow, although he could have been, wasn’t concerned over the issues. Either way, the narrative that has come down about Horsham in the late Victorian period is one of a country market town ticking over, rather than, as is shown below, a town where cutting-edge debates took place. Debates that have echoes today.

MARKING A CENTURY

Some two weeks later, after agreeing to the paving, Horsham, along with the nation, celebrated the centenary of the Sunday School movement. On Sunday the 25th at 3pm, there was a religious service held in the Congregational School Room, Albion Road. Then two days later, on the Tuesday, “A DEMONSTRATION will be held in Horsham Park, (by the kind permission of R H Hurst., esq. And Mr Prewett)” as the poster, printed by R. Laker Snr, Horsham, boldly declared before announcing that the children would congregate at the school room at 2pm and then march through the Town to the park “Headed by the BAND” with games and a free Tea for the children at 4, with Teachers and Friends having theirs at 5.30 at 9d. The Band was probably the Fire Brigade Band which on previous occasions had doubled-up as the Town Band.

The Congregational School Room at Albion Road saw this year the formation of the Horsham Mutual Improvement Association. Dorothea Hurst records its existence in her revised history, published in 1889; not under the aegis of the Association but as a user of Albion Hall, noting that it “is a large plain building, situated in the Albion Road, capable of containing about 300 persons, erected by subscription, through the efforts of the Nonconformists, and used by them for a Sunday School; but also very frequently hired for different public meetings, especially temperance Meetings and those of the Mutual Improvement Society ”[10]. That is the only mention in her book of this group. This would tie in with the national picture as noted by Jonathan Rose: “these institutions are scarcely mentioned in studies of labour history. Richard Altick and E.P.Thompson appreciated the critical role they played in adult education, but could locate very little information about them. Though they were ubiquitous in Victorian and Edwardian Britain, they left few surviving records. In most cases, they can only be reconstructed through the memories of their members”.[11]

Fortunately for Horsham, the minute book of Horsham’s Association has survived and it provides a rich vein that hasn’t been mined before. In addition to the minute book the Parish Magazine, which started in 1884 and is discussed below, also contains brief accounts of the Association meetings, as does the local press. What is clear is that the Association conforms very much to the picture outlined by Rose, whose study can provide a national context; thus making the Horsham story both less and more relevant: less in that the Association was following national trends, and more because it shows that Horsham was increasingly absorbing, and being absorbed into, the national scene; Horsham was not an isolated part of late Victorian Britain, but a fully paid up member.

The minute book reveals that a preliminary meeting of the Association was held on 2 December 18?? in the Old School Room Springfield Road, with a formal meeting held the following day. At this meeting the key purpose of the Association was decided upon: “That the object of the association be the mental and moral culture of its members. That for the attainment of this meetings be held for readings, Discussions, for reading of essays and such other pursuits as may be deemed desirable”. This can be seen as the classic model. “The mutual improvement society was a venture in cooperative education. In its classic form, it consisted of a half dozen to a hundred men from both the working and lower- middle classes who met periodically…Typically at each meeting one member would deliver a paper on any imaginable subject-politics, literature, religion, ethics, “useful knowledge”- and then the topic would be thrown open to general discussion.. The aim was to develop the verbal and intellectual skills of people who had never been encouraged to speak or think”[12]. As we shall see, Horsham’s branch covered most of those themes.

So less than two years before, the Horsham Literary and Scientific Institution had closed its doors and now the self-improving drive of the Victorian mind saw to it that a new institution be formed[13]. This shouldn’t be that surprising, for the chief protagonist of self-improvement was Samuel Smiles, whose worldwide best seller Self Help, published in the same year as Darwin’s Origin of the Species, 1859, was based on lectures he gave to the Leeds Mutual Improvement society in 1845.[14] A week later, 9 December, the first public meeting was held; an entertainment consisting of readings and “recitations vocal and instrumental music”. At the next committee meeting a piano was hired for the season for £2.10/-. At the same meeting it was decided that there should be weekly public meetings. At the final public meeting of the year “a novelty was introduced into the entertainments of the Horsham mutual improvements Society”, according to the newspaper account pasted into the minute book of the Association from where the information comes, “in the shape of a discussion as to the merits and demerits of smoking”. The public meeting decided smoking was not beneficial.

SMOKING: THE DEBATE

At the time of writing this, 4 January 2007, the Government had just proposed increasing the age at which it was legal to buy tobacco, from 16 to 18. It is interesting, therefore, to read of a debate in Horsham on the effects of smoking, a debate that must have been taking place elsewhere, but which has largely been ignored. As the newspaper reports, “Mr Alfred Scrase undertook to defend, and Mr. Jury Cramp to oppose the use of tobacco, – In the course of an ably written paper, Mr. Scrase contended that many reasons might be adduced in favour of moderate smoking. He quoted a number of medical testimonies in favour of smoking and also cited no less an authority than the Lancet, and the well known “Family Doctor”, of Cassell’s Magazine to show that smoking might be indulged in without very injurious effects. The women, and even the children, of Burmah all smoke, and are still of average health. Our soldiers and sailors smoke, and none are, as a rule, more healthy, stronger, or capable of more endurances…(and smoking) “when moderately indulged in, neither injurious to health, to morals, or to society, but had been and was still, the comfort and consolation of many millions in all parts of the world (cheers). – Mr Cramp followed with an equally able and argumentative essay on the negative side of the question. He based his objections chiefly on the physical bearings of the subject, and contended that the whole body of man was very seriously affected by the poisons of nicotine in the tobacco. After detailing many diseases to which smokers are known to be subject, Mr Cramp urged that morals were not improved, but otherwise, by smoking, as smoking often gave a keen thirst for strong drink. “Mr Cramp then argued that the £15,000,000 spent yearly on tobacco and cigars could, if saved would benefit Society. “At considerable length the reader combated the medical evidence in favour of smoking, and also contrasted the rival opinions of eminent medical men. The discussion was then continued by Mr Harrington, Mr Baxter, and others, and the interesting and instructive debate closed”. (The minute book of the Temperance Society given to Horsham Museum by Cecil Cramp has a large number of medical accounts published in the press concerning the issue of smoking. It was surprisingly a “hot” topic of debate – leading to the question: why did it take over 100 years for the debate to become as active again?)

Although there were many other societies around or recently formed in Horsham; for example, the Chess Club in 1879[15], The Mutual Improvement Association is one of the most interesting because it tells us what issues people in Horsham thought about. There are obviously a raft of caveats: for example, we don’t know how many or who attended the lectures, whether it was just a “politicised” minority, if there was a genuine interest or was just something to do. But, and an important but, it does indicate that there was a level of political consciousness in Horsham, Horsham wasn’t merely a receptive, passive place ignoring the issues of the day, but was engaging in the debate, and unlike some of the groups the Association was not part of a larger formal structured organisation, but did draw on what other Associations and Societies were doing, though this wasn’t identified in the minutes. That being said, the Horsham Association was created and developed within Horsham to meet the needs of Horsham folk. For that reason, the minute book will be looked at in more detail.

The Association ran a full programme of lectures, readings and musical evenings; the latter being the most popular; each season, running from September to May. The minute book refers to a lending library with it being open every Thursday from 7.30 to 7.45. The fine for an overdue book was 1d per seven days or part thereof. The books were to be selected by the committee. At the same meeting, on 11 January 1881, it was decided to hold classes “for the mutual improvement of members in elocution and for criticism – at such times as it should deem expedient”.

The first meeting was held on 4 February, but the audience was small. The secretary was also “instructed to make inquiries at South Kensington in reference to the formation of science & art classes”[16]. This was the beginning of art teaching in Horsham, as will be shown later. Two days later, on 13 February, a lecture was held by Rev S. Evershed “On the formation of a habit of scientific inquiry”, with a small audience. A week later an evening devoted to “local and instrumental music – readings and recitations” was held but the “weather being most unpropitious”, the audience was “fair”. Interestingly, each evening’s entertainment had its own programme printed identifying the piece and the performer.

On 3 March J. H. Freeman F.R.A.S gave a lecture on Some of the wonders of the Heavens, which was “listened to by a large and enthusiastic audience”. On 5 May 1881 the Committee decided to hold a public meeting in the Town Hall on 11 May to see what response there would be to forming classes linked to the South Kensington scheme. Unfortunately, on the day, the audience was small so they decided to commence with art. Horsham would now have a formal art class that would see many notable artists emerge and provide Horsham Museum with a wealth of local topographical views.

To help the class on its way, on 8 February 1882 a “Grand Evening Concert in aid of the Art Class… by the Horsham Glee Club” was held at the Albion Assembly Room, raising £10 –14 –6d. The second annual report would record with pride the following: “The Art Classes which have been established in Horsham, though not ostensibly connected with the association are in reality one of the good fruits of a desire for Mutual Improvement and ? culture which is the object of our association. It may be remembered that they were first suggested by our President at one of our meetings and they have been established, on, we hope, a permanent footing by the ? and great personal assistance by one of our vice presidents Mr Alex Wood.”

The next season started with a musical entertainment. Membership was a shilling, with admission to the Entertainments being 1/-, 6d and 2d, members free, paying half price for the 1/- seats. Public meetings would be fortnightly, with meetings for reading English literature held every alternate week. The first entertainment of the season was a great success, as was the reading. The table below sets out the lectures identified in the minute book for the1881/2 session along with any comments made about them:

| DATE | SPEAKER | SUBJECT | COMMENT |

| Wednesday Oct. 12th 1881 | J H Freeman F.R.A.S., F.C.S. | The Marvels of Chemistry | Illustrated with numerous experiments. A large audience £2. 9/- taken at door |

| Nov.10th 1881 | Rev. Robert Wilson | Life on the Nile | “very interesting was listened to with marked attention by an intelligent and large audience, £2-7-8 taken on door |

| Nov 17th | Alex Wood M.A. F.S.A. | Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice- its plot-his characters and its teaching | “The lecture displayed a large amount of thought and research…audience small 5/4 taken at door |

| Dec 8th | Sir Henry Fletcher Bart. M.P | An account of Sir Henry’s Visit to Ireland | Highly interesting. “The audience was a large and fashionable one – £5-6-9 taken at door” |

| Thursday Jan. 26th 1882 | W E Hubbard Jun. | Fair Trade; Free Trade; and the General Principles of Business. | “This lecture was well attended- it was followed by discussion in which the following gentlemen took part- Free Trade- W Lintott, J G Brown, J Harrington and W E Hubbard Esquires. Fair Trade R Ramsden Esq £1 16 2 ½ “ This lecture was promoted with a flyer |

| Thursday Feb 16th 1882 | Rev. C F Overton M.A (Vicar of Warnham) | South Africa | “Large and fashionable audience – Highly interesting lecture.” £2-13-6 The lecture illustrated by diagrams |

| Feb 27th , March 6th & 13th | Dr E L Bostock | St Johns Ambulance Association | “the audiences were not large which is much to be regretted – the lectures being highly interesting. |

| March 30th | Sir John Bennett | The Natal | “Illustrated by diagrams and models” £1-1 |

According to the second annual report the Association had nearly 300 members. “The lectures without an exception have been of a highly instructive as well as interesting character – and it is believed they have conduced greatly to the mental improvement of the audiences”.

The lecture programme itself shows how certain long-term issues of the day were played out in Horsham: namely, the Irish Question and South Africa. Although the lecture was an account of Sir Henry’s visit to Ireland it would have been set against the background of the discussions taking place over how Ireland was to be governed; a debate that was ripped apart by Gladstone’s insistence in 1885/6 that the Liberal Party would back the establishment of an Assembly, a subordinate Irish Parliament. This was the Liberals’ “Corn Law”; the issue that helped to reformulate Liberal and Conservative ideology and allegiances in the last decades of the 19th century.[17]

The South Africa debate in Horsham followed almost a year from the shattering defeat of the British by the Dutch Boers. South Africa was hot news following the defeat at Majuba Hill on 27 February 1881.[18]

Not only was Southern Africa of interest, but so was North Africa and, in particular, Egypt; and Egypt meant the Nile. Egypt had for various reasons become an economic basket-case leading to its bankruptcy in 1875-6. Britain and France intervened along with other European countries to stabilise the situation. Their efforts led to a revolt in September 1881 by four Egyptian colonels who under the slogan “Egypt for the Egyptians” garnered much local support. This frightened the British and French, who thought the Egyptians might default on their debt repayments that had been formulated to resolve the country’s bankruptcy. This led to further engagement in Egyptian affairs, eventually leading to the British invasion of Egypt, at the behest of the Khedive, on the 16 August and the defeat of the Egyptian nationalist forces on 13 September 1882; after this Britain began its occupation of Egypt. It must also not be forgotten that there was a religious angle, with the story of Moses, a story that was told in the schools and Sunday schools of Britain. This particular story may have had more resonance in Horsham, as the medieval wall paintings recently refurbished in the parish church portrayed Niletic plants and animals. In addition there was the ongoing romance of the Nile itself, the search for its source capturing the imagination, with Stanley having concluded his search in 1877. As the Vicar of Warnham was giving the lecture it is likely that the biblical element came to the fore, but the contemporary geo-political nature of the lecture must not be overlooked. In addition to the lecture a husband and wife team who had links with Horsham was also involved with Egypt, Wilfrid and Anne Scawen Blunt,

SCAWEN BLUNTS AND EGYPT

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt was born in 1840 at Petworth House, the second son of Francis Scawen Blunt of Crabbet Park, Poundhill and Newbuildings Place, Southwater. His ancestor had owned Springfield House where they had entertained John Baker (see vol.1). At the age of 18 he joined the diplomatic service, serving 11 years in Europe and South America. He was blessed with good looks, so actively enjoyed the pleasures of female company, becoming, amongst other things, the young lover of Catherine Walters, the celebrated or notorious, depending on whose view one takes, courtesan Skittles. In 1875 John Murray, Byron’s publisher, published Blunt’s first book of poetry Sonnets and Songs by Proteus, where Skittles became Esther. According to the critic John Murray, the poetry was “truly of the grape, not of the gooseberry”. In 1869 he married Byron’s granddaughter Lady Anne Isabella Noel King, heir to the Milbanke fortune. Now wealthy, Scawen left the Foreign Service.

With the death of his brother and his sister of tuberculosis in 1872, he became owner of Crabbet Park and Newbuildings. He and his wife then departed on their travels in the Near East and Arabia where they would make their name for courage and expertise. Their accounts would be, and still remain today, classics of travel writing, with his wife’s accounts of Bedouin life being almost anthropological in its detail.

In 1878, and mainly through Lady Anne’s money and interests, they decided to form a stud in England at Crabbet Park. They met with the sheikhs famed for horse breeding and over the next decade they actively acquired breeding stock including the remnants of the Abbas Pasha collection in Egypt. It all started when they purchased a pure-bred Arab stallion, Kars, for £69 and founded their celebrated Crabbet Arabian stud. There is one local story that relates to the Blunts’ interest in Arabian horses. In the same year they bought a stallion called Pharaoh for “£192 6s, a 14.3 dark bay with black points, celebrated among the tribes as “the handsomest colt bred by the Sebaa for twenty years…The carriage of his tail was magnificent and he had ‘eyes like the human eye, oval and showing the white’.”[19] On 29 May 1882 the Blunts would show Pharaoh off in Horsham. Lady Anne had painted Wilfrid “bushy – bearded and in a Bedouin head-dress and robes, seated with casual grace upon the rearing stallion Pharaoh, finishing it in November 1881” Obviously both took great pride in the horse, yet, as Anne wrote, the horse was passed over for a “mongrel”. Anne believed it was down to either the mongrel’s owner being related to the judge, or because bondholders, those that held bonds covering Egypt’s debt, flocked to the show and they “loathe the name of Blunt”[20]

In 1882 the Blunts purchased a 37-acre walled garden outside Cairo named Shaeykh ‘Ubayd: this was to be their winter home and where they created a second stud. By now Lady Anne had made a name for herself having published two travel books, The Bedouin Tribes of the Euphrates (1879) and Pilgrimage to Njed (1881). Although Lady Anne is credited as the author, they were based on her journals but rewritten by Scawen. Lady Anne did however become fluent in Arabic and developed an encyclopaedic knowledge of Arab horses, writing two books which her daughter would eventually incorporate in her books on the subject. Anne would also translate original Arab texts which Scawen would put into verse and have printed.

Back in England Scawen Blunt, now forty, entered the political arena trying to make England a liberal place and to regenerate Islam. (In today’s 2007 climate of “islamaphobia” this may seem strange.) Whilst rewriting his wife’s journals he thought about the political dimension, producing a number of articles which would be republished in 1882 in the book The Future of Islam. The book The Future of Islam sets out his early ideas; ideas which nearly changed the face of British imperial interest. As he writes in his Preface:

“These essays, written for the Fortnightly Review in the summer and autumn of 1881, were intended as first sketches only of a maturer work…Events however, have marched faster than he at all anticipated…the French, by their invasion of Tunis, have precipitated the Mohammedan’s movement in North Africa; Egypt has roused herself for a great effort of national and religious reform; and on all sides Islam is seen to be convulsed by political portents of ever-growing intensity. He believes that his countrymen will in a very few months have to make their final choice in India, whether they will lead or be led by the wave of religious energy which is sweeping eastwards….To shut their eyes to the great facts of contemporary history, because that history has no immediate connection with their daily life, is a course unworthy of a great nation; and in England, where the opinion of the people guides the conduct of affairs, can hardly fail to bring disaster. It should be remembered that the modern British Empire, an agglomeration of races ruled by public opinion in a remote island, is an experiment new in the history of the world, and needs justification in exceptional enlightenment; and it must be remembered, too, that no empire ever yet was governed without a living policy. The author, therefore, has resolved to publish his work, crude as it is, without more delay”[21].

Blunt then informs the reader that he has revisited the country setting out the current situation, before apologising to the Mohammedans for any error that he may have introduced because of his ignorance. He then goes on to say “he has a supreme confidence in Islam, not only as a spiritual, but as a temporal system the heritage and gift of the Arabian race, and capable of satisfying their most civilised wants; and he believes in the hour of their political resurgence.”[22]

Blunt’s position was simple: an Islam led by, and based around, Egypt was preferable to that based around the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Empire had grown rapidly from its Turkish heartlands in the 15th and 16th centuries, creating a powerful entity that separated Britain, France and the Dutch countries from their far eastern colonies. However, their power was declining in the face of growing western expansion, which led to a jockeying for positions, a feature exacerbated by the Suez Canal. Britain and France had a choice: do they let Egypt grow and become independent of the Ottoman rule, or do they allow it to be subsumed within the weakened Ottoman Empire? Blunt through his contacts had met Gladstone, and initially had great success persuading him to pursue the goal of Egypt for the Egyptians. But by May 1882 Gladstone had changed his mind and Alexandria was bombed. Blunt was banned from Egypt. Blunt, the anti-imperialist, had nearly succeeded in stopping imperial aggression. In retaliation Blunt wrote and published The Wind and the Whirlwind in 1883, which predicted the fall of the Empire as the weak would eventually strike back. [23]

Blunt now involved himself in other nationalist issues; not just Egypt but India and Ireland. His wife would concentrate her efforts in the Arab stud.

In some respects it is possible to see these lectures as part of the hunger for news. In 2006 the BBC celebrated 40 years of “From our Own Correspondent”, a radio broadcast giving the personal approach to a topical subject, or story that interested the reporter in the region of the world they were based. In 1880 there was no such system in place; the major newspapers had journalists in the field[24] but the accounts were reporting on events rather than the context, though part-time Southwater resident Scawen Blunt had written some perceptive articles that had been published in Fortnightly Review and republished in book form in The Future of Islam, in 1882, but for the majority such accounts would have been little-read.

It should not be forgotten that the Mutual Improvement Society gave public readings. A nationwide movement started in the 1850s where extracts were read from books at a penny a time which lasted up to the end of the 1890s, and in one survey of working class interviewees reading aloud had been practised in half of their homes[25], so listening to a talk was the preferred method of finding out. Horsham was able to tap into the network of personal contact to find out the context; to have a first-hand account. As was shown with the Horsham Journal published by Albery, foreign press stories were reprinted; for example, the praise of Sir Fitzgerald in India; there were letters going between Horsham people and Horsham émigrés which were probably being circulated, but these lectures gave a very public account of the world outside Horsham, a window on the world. The lecture on Free Trade, Fair Trade would have no doubt covered some of the prevailing economic arguments over the Empire, arguments that by the end of the century had led to questions of Tariffs to protect home industry and Imperial concessions[26].

The following committee meeting after the AGM, on 23 June, saw the proposal by Mr Frost “to hold a loan exhibition of objects of art during the month of October next…for the benefit of the art class and the association”. Unfortunately little survives concerning this exhibition but it would be unsurprising if George Bax Holmes and Thomas Honywood didn’t lend material from their own collections to the exhibition, for they had done the same some eight years earlier in 1874.

THE LOAN EXHIBITION AND PROTO-MUSEUM

A reference in 1882 Kelly’s Directory of Sussex[27] suggests that the idea of a museum was in the air at Horsham. The Directory was probably referring to the Loan Exhibition, or as the idea is tied directly to the Volunteer Fire Brigade, it is more than likely that it was the curios and antiques owned by Captain Honywood (see below). However, Horsham had two individuals who referred to their own collections as museums: George Bax Holmes and Thomas Honywood. Bax Holmes, Horsham’s dinosaur hunter and the senior of the two, had clearly allowed people in the town to view his finds, as noted by Dudley as early as 1836. If they could not, then Dudley[28] would have been more guarded. Equally, the concept of the museum wasn’t alien to the world of Horsham. For example, Sarah Hurst, some six years after the foundation of the British Museum in 1753, tried to visit it on one of her stays in London.[29] In Brighton Gideon Mantell had created his own Museum in the 1830s which was open to view, so to Bax Holmes the idea of showing his specimens within a museum setting would have been natural.

But it was the Great Exhibition of 1851 that caught the public imagination, for here objects were exhibited to glorify the work of British industry and the Empire, as well as to marvel in man’s ingenuity. The tone was wonder and awe rather than pure education. It wasn’t the Great Museum, but the Great Exhibition, and it was to that event that Henry Michell took the schoolchildren of Horsham. Henry visited the Great International Exhibition in 1862, which he viewed with less enthusiasm.

“Exhibitions” had become part of Victorian life, and so the while the great and good of Horsham didn’t discus the creation of a “Museum”, they did discus the idea of an “Exhibition”. And so in 1874 Horsham mounted the Horsham Loan Exhibition to which Holmes lent some of his specimens. The Horsham Advertiser described it thus: “a grand exhibition of ancient and modern articles”; which were on view to the public for two weeks in January.[30] Although the local press referred only loosely to beautiful specimens of natural history, a better description of Holmes’ contribution appeared in Nature of the same month, via a letter written by a Thomas Cowan who had clearly been well-briefed by Holmes.[31] George’s fossil remains may have caused some local comment, but by now the discoveries on the Continent and, particularly, Belgium would have diminished their scientific importance, though not local interest.

The other lender would probably have been Thomas Honywood, the noted and fêted Captain of the Fire Brigade, photographer and inventor of “nature printing”, as well as amateur archaeologist, who has previously been mentioned for his Mesolithic finds. He probably lent some of his flints, and possibly the Horsham Hoard of medieval pottery.

Horsham was developing a culture of exhibitions based around core collections built up by local people, who viewed the objects as a means of understanding the past and world around them as well as providing an artistic background, for the exhibition was put on in order to raise funds for the Art class.[32]

Perhaps it was the strong link between South Kensington and the art class’s formation that encouraged the idea of another loan exhibition. Equally, Horsham folk were avid attendees of exhibitions, especially as now it was only a maximum of two hours away by train. So in 1884 there were at least two outings by Horsham folk to see the Healthy Exhibition, followed by a visit in 1886 to see the Colonies Exhibition; and Thomas Honywood exhibited at the Inventions Exhibition in 1885[33]. The Exhibition was an important part of the controlling influences of Victorian society, for you saw works created by others and were thus (generally) struck by your own inability and/or awe; and, more importantly, you were seen by others and you saw others – thus reinforcing codes of behaviour.

There is one other remarkable feature about Horsham that needs to be raised, but doesn’t sit comfortably within the narrative: that of prehistoric life. Today we sit easily with the concept of prehistory, of a human past stretching back thousands of years. The opening pages of this history explored Horsham’s past without any theoretical or conceptual context. We know of it and accept it as fact. Yet that is only recent; somehow, in Horsham, a town of around 5,000 people, two men would co-exist within the same timeframe who would be willing to think ‘outside the box’ about the past. George Bax Holmes would actively search out fossils from the pre-‘Adamatic’ period, and take onboard revolutionary ideas.[34] Whilst it might be easier to think of dinosaurs roaming the planet before the emergence of man, the notion that Britain was populated by humans with a past that disproved the Biblical teachings was even more far-fetched. Today we assume that Darwinian evolution is the accepted way of thinking about the past, yet Origin of the Species was published in 1859 and the follow-up The Descent of Man, which put it within a human context, was only published in 1871 and there was no mass conversion to evolutionary acceptance.[35]

Whether these ideas had widespread acceptance within Horsham is questionable: interestingly, none of the Horsham Mutual Improvement Society lectures covered such issues. Therefore, the reason why the exhibition was an exhibition rather than a temporary museum was because such issues were not faced: it was a display rather than an education. In fact, it wasn’t until 1893, some six years after Bax Holmes’ death, that Horsham had a ‘public’, rather than private, Museum, with the foundation by the Free Christian Church of a Museum Society.

The Mutual Improvement Society continued to flourish with an active lecture programme, though with the replacement of the secretary, the minutes are not so enlightening. In 1885 the Committee decided that “ladies and minors under the age of 18 be not allowed to vote in any of the debates”. (Nationally this was often the case, with women excluded from debates, only opening up towards the end of the century[36]). The same year, debates were proposed on “Free education”, “Novel reading; is it injurious or beneficial to the general public” and “Compulsory National Insurance”; however, National Insurance was removed from the list and replaced by a debate on “Radicalism” and a new subject of debate: “The Liqueur Question”.

The following year 1886 Mr R. H. Hurst was appointed president of the Debates; such was the Association’s growing status. A letter was received from a Mr Turner, of the Crown Inn, with suggestions for debates:

“Subject No 1.,

That the “Unprecedented” increase of “Infant and Children” “Mortality”, during the months of Janry, Febry, Mar, and April, in the present year, was due to the “Unsanitary, defective Town Sewage” of Horsham.(the issue of infant mortality will be covered below)

Subject No.2.

That “Trades Unionisms” is a Financial and Social Evil”, to the British Empire.

Subject 3

That the “? Men” members of Parliament hitherto returned have not “Financially nor Socially” benefited their class, but shown themselves “obstructive to Legislation” by their Ignorance and waste of valuable legislative time”.

Obviously written with some passion, the Committee’s response was that Mr Turner was asked to “formulate his resolutions more in accordance with the etiquette of Parliamentary usage”.

The same year it was decided to move from Albion Road to the Kings Head Assembly Room. In November 1886 the Rev. H. B. Ottley proposed the Association provide “Penny Entertainments on Saturday Evenings”; the Committee felt that it “couldn’t undertake it at present”.

In 1888 the Association printed a programme or, as they called it, ‘Syllabus”, for the first session, from October to December. The highlight undoubtedly was on 6 November when “Mr Charles Dickens. Reading from his Father’s Works: “David Coperfield” and “Bob Sawyer’s Party,” from “Pickwick”, at the Kings Head Assembly Rooms. Apart from entertainments, the programme consisted of two papers with debates, one of which was on Some Social Reformers, and two lectures. Mr Ash’s lecture on 29 October was with “dissolving views”, “My visit to Russia, how I went and what I saw” Illustrated by means of a Triple Lime-light Apparatus.” Professor Hulme’s lecture on 10 December was “The Pleasure of a Country Lane”; neither of which seem as relevant as those at the start of the decade, but both were, in their way; especially the country lane, as will be shown later.

Before leaving the Association, one comment needs to be made concerning the meetings; one that stands out because it is unexpected. At the bottom of some of the musical programmes is the comment “The Audience are requested not to leave their places until AFTER the National Anthem has been sung”. The image or perception of a highly patriotic and deeply royalist people in Horsham may not be the case at all; perhaps some of the audience had republican sympathies; after all, the Queen withdrawing herself from the public was a concern to the Government, particularly in the 1870s, though by 1887 as we shall see, in Horsham and elsewhere, Victoria had been “rehabilitated”[37].

The perception that Horsham was a quiet backwater during this period is also countered by a scrapbook made by James Harrington of 11 Albion Terrace in 1879/80. In the pages of an 18th century Latin maths book Harrington pasted in cuttings from various newspapers relating to the School Board, to which he was elected in 1879. The newspaper cuttings provide an interesting picture of education in Horsham, starting with a notice culled from The Horsham Advertiser 14 February 1880.

The cutting includes a letter sent by the school board to the authorities requesting that the fees be reduced in the outlying areas of the town from 2d to 1d., with St Mark’s and St Mary’s remaining at 2d, the reason being:

“Broadbridge heath, a purely agricultural district; Roffey, a most destitute district, certainly the poorest locality in Horsham; Trafalgar-Road in which the principle number of the inhabitants are mechanics and labourers, with small wages and some large families; east parade is situated in a district similar to Trafalgar- road with a fair proportion of labourers. We urge our requests upon the grounds that as compulsion is used, advantages ought to be given as far as possible to the poorer ratepayers…We also feel that as children are debarred up to the age of 13 years from earning anything for the household, advantages should be afforded as far as consistent with prudence”.

The cutting goes into a great deal of detail which is fascinating, but out of place in a Horsham history; e.g. the hanging of a picture of the crucifix in Roffey School or the provision of a lavatory in the same school; that the Union children, those who were at the workhouse, attended this school and the fact they had to attend religious instruction, thus reducing the attendances at the school; the amount of coal required, the classrooms being too hot.

The above cutting reveals that Horsham had, and was seen to have, a zoned town with distinct areas of poverty, including those where agriculture was prominent. Schooling was compulsory, in Horsham at least, for the Daily News of 1880 reported that local authorities will be encouraged to pass by-laws to enforce attendance. The fact that children couldn’t work till they were 13 was seen as a definite hardship and a modern introduction. Later it would be noted that the School Attendance Officer reported two boys hadn’t been to school and the Board had resolved to have a magisterial order to send them to an Industrial school. In addition, at that meeting they agreed that the number of times of non-attendance constituting neglect should be reduced from ten a fortnight to five; thus in effect increasing school attendance.

The minutes of the meetings as reported in the local press raised three issues which are very modern in approach and debate, within Horsham; namely: corporal punishment, the contract between state and parent, and religious involvement within education. Two of the issues caught the attention of the national press. In October 1880 The Teacher, a national newspaper reported in heavily sarcastic tones the policy the school board had adopted regarding corporal punishment; namely, that no child should receive corporal punishment by a teacher without permission of the Board. As The Teacher commented:

“The grotesque, thick-witted insolence implied by the regulation goes beyond the limits of caricature; but, after all, a good many Boards such as that presided over by Mr. Frost are really caricatures of the worst London vestries, so anything in their proceedings that seems unfamiliar to metropolitan individuals need not be reckoned incomprehensible…The Reverend being whom we have just proved to be a teller of falsehoods encouraged the staff by the following statement:- “if,” said the Reverend being, “a teacher struck me, I should give him one back….Now, in the catechism which Mr Frost and his species love to impart to the infant mind, children are enjoined to order themselves lowly and reverently before their pastors. Mr Frost is a pastor, so any child who does not strike at a teacher when punished is disobeying his pastor, and thereby imperilling his soul’s health. Therefore all loyal children in Horsham are justified in refusing to brook chastisement tamely…Mr Frost is an interesting specimen of his species…”

Later in the correspondence the Reverend Frost gives his reason for what today would be seen as an enlightened attitude:

“The Chairman said that his view of corporal punishment was that the position of the Board in the town was different from what it would be if the schools were voluntary. In the latter case a parent could take his child away at any time if he were dissatisfied, but as matters really were every parent was obliged to send his child to school whatever treatment it received, and there was no court of appeal but the magistrates’ Bench” He went on to say when the parents had given permission to the teachers he “felt no difficulty in supporting the resolution. He was opposed to the teachers having unbounded liberty to punish the children”.

Further discussion took place within the committee concerning the level of punishment and where, if the child was to receive corporal punishment, the blow or blows should take place; even asking for medical advice. A suggestion was put forward that a maximum of two blows and on the back (Dr Bostock said “the back was made on purpose for the cane (laughter)”.

The debate itself may surprise readers, because of the assumption that “in boys’ school every sum wrong, every spelling mistake, every blot, every question which could not be answered as the fateful day of examination drew near, was liable to be visited by a stoke of the cane”[38]. Or that “Caning in school was ubiquitous”[39]. Yet, in a survey of 444 children who were born between 1870 and 1908, “at least a quarter of working-class children, a third of other children, and 42 percent of all girls suffered little or no such punishment.” Whilst a number of other respondents stated that the punishment was often strict but just, suggesting to Rose that “the resentful were outnumbered by those who reported that corporal punishment was invariably fair, or infrequent, or simply not done”[40]. Having said that, Collyer’s school between 1869 and 1883 was ruled with the cane of Richard Cragg, the Headmaster, and the Usher John Williams, both remembered as “floggers”[41].

The issues raised in the debate are also revealing, and the fact that Horsham appeared in the national press probably indicates a wider discussion going on, rather than a localised one, for often it is easier to discuss local specifics than grand generalities, so the comments were not relegated to the “and finally”, but to the main editorial. What is apparent is that children were being seen in a different light. Instead of society needing protection from children, children needed protection from society. In fact, two years later after the debate in Horsham, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, NSPCC, was founded.

CHANGING CHILDHOOD[42]

The late Victorian/early Edwardian period saw society’s involvement with and about children change. This is not the place to discus the changes in any great depth, but the following will give an indication of the changes taking place and thus put into context the Horsham story.

In 1868 Louisa May Alcott could write her popular novel Little Women; children were seen in some regards as little adults. By the end of the century Barrie could write Peter Pan, about a child that doesn’t want to become an adult, but also about the magic of childhood. In addition the school leaving age rose: in 1880 it was set at 10, 1893, 11 and 1899, 12 with the ability for local authorities to raise it to 14 in 1900, though few did before 1918. In addition, the number of children being born was declining.

1860s 6.16 children

1870s 5.8

1880s 5.3

1890s 4.13

1915 2.43

In marriages which lasted 20 years or more the family size declined, which might make each child more valued, a view which advertisers picked up on with their sentimentalised view of the older child being seen as a rascal; cheeky, rather than a wild, abusive criminal. An example of this can be seen in the Parish Magazine when the vicar in 1884 appeals for funds for the East London Children’s Holiday Fund. Here the sick children were sent into the country for two, and on occasion, three weeks to have the benefits of “pure air and country pleasures”. The report of the visit is couched in sentimentality: ” The children have benefited in every way, and many thanks are due to the cottagers for the kindness and care with which they have been treated…The majority of these little Londoners have never spent more than a few hours in the country before, and were half-astonished to find that “buttercups” did not grow on hedges, nor strawberries onraspberry canes”.[4] The idealisation of the countryside over urban life will be explored further in this history, but the view of the East End child as innocent of nature rather than a “Fagin gang member” is clearly expressed. Some two years later, 150 children came to Horsham and the six children who misbehaved was put down to exuberance of youth rather than criminality.

This change manifested itself in the political sphere with changes in public policy. Prison was no longer seen as the right place to send children, and hospitals created children’s wards or even specific hospitals rather than within the women’s wards. In 1885 the age of consent for girls rose from 14 to 16, whilst incest, a taboo subject, was given a public airing with mothers given advice on how to deal with the subject[44]. Four years later in 1889 the Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act was passed which carried a fine or prison sentence for neglect, abandonment or ill-treatment of children. In the same year the Poor Law Act gave the Guardians the authority to terminate parents’ rights over abused children. It was further tightened in 1894 and 1899.

There was also a growing awareness of adolescence throughout this period. Some of the ideas were fanciful but all were concerned with the changes that took place in children between childhood and adulthood; a period known as youth. There were also concerns expressed about the lack of deference to adults and the growth of gangs, of “loafers“, hanging around on street corners cigarette-smoking and gambling, while girls would be getting “a dangerous craving for excitement” through reading “mawkish novelettes“. There was also a growing attempt to organise children’s leisure time. In the early 20th century 80% of 5 to 14 year olds attended Sunday school. There was the Anglican Girls Friendly Society of which Horsham had a branch, as recounted in the parish Newsletter. Other groups were soon established: the Band of Hope, Boys Brigade, Church Lads Brigade and in 1907 the Scouts, which interestingly asked Scouts to show obedience to King, Country and even employers but not parents. At the other end of the age range the age at which children could be taken by schools rose. When compulsory education was first introduced it was used by working class mothers as a nursery, but between 1901 and 1911, under-3s were taken out of the system and the number of places for 3-5s drastically cut back.

By the First World War there was a structure to childhood, which was mimicked or followed in the commercial world with, for example, publications aimed at age-related markets. Infants, juniors and adolescents had arrived.

BIRTH CONTROL

The figures in the table above show a marked decline in birth which was not down to rising infant mortality: simply stated, people were practising birth control. The reasons why this happened are too complex to go into here. However, in 1908 the Registrar-General calculated that 79% of the population decline was due to “deliberate restriction of child-bearing“. In 1879 The Malthusian League was formed to promote smaller families, offering advice on how this could be achieved. Chemists were promoting various remedies, but birth control clinics didn’t appear in working class areas until after the Great War, suggesting that abstinence was one of the main methods. In middle class homes respectable opinion frowned on artificial interference, linking it to the grubby world of prostitution, and just above abortion. Doctors would give lurid warnings about contraceptives claiming they led to cancer and, in the case of women, hysteria and galloping nymphomania. One Doctor was struck off in 1886 because he published his birth-control manual – The Wife’s Handbook – in a cheap edition[45]. But what is clear is that control was taking place, and on a grand scale, which reflected changes in society; a society trying to cope with, incorporate, and advance, issues about gender[46], family policy, adulthood, childhood and images of self [47], amongst many others.

Unfortunately we don’t know the date of the lecture, but we have in the Museum’s poster collection one for men only. As the poster proclaims: “Meeting for Men Only (15 years and upwards) Dr Fairlie Clarke will lecture on Purity at the Town Hall, Horsham at 8.15 pm Monday November 6th The Vicar of Horsham in the Chair. Come and Hear your old friend”; as the notice was for public display, the subject matter was kept discreet, but as it was for men only and concerned purity it was probably about sexual matters, as far as such matters could be discussed. The poster itself seems to date from the 1880s to around 1920. At such a time there was a great deal of discussion about racial purity, feeding out of the works by Darwin, but feeding into, in its extreme form, the ideology of the Nazi party. Was the poster publicising such a talk? Unfortunately, the title is too elusive.

The exchanges which were recorded in the press concerning the views of the Horsham School Board on caning are revealing, and not just in respect of the view of the nature of discipline and childhood.

The Teacher newspaper was arguing that the teacher had a certain level of responsibility and what we would understand today as professionalism; an ethical code of conduct that marked them out as being above the rest of society with regard to imparting and controlling children. The Teacher viewed any limitation of their power as an attack on their status; hence the virulence in its comments on the Chairman of the Horsham Board. The Chairman, Mr Frost, on the other hand was taking a more societal view arguing in effect that as the parents could not withdraw the children from a school, the school board had to look after the parents’ interests, in effect be a check on the behaviour of the teacher, their employee. It is a remarkably mature and sophisticated level of debate, which is still being played out today. In effect, whilst the issue, or to give a medical analogy, the symptom, was the use of corporal punishment, the real issue, or illness, was the degree to which the school board or state should protect the child and act as the child’s guardian when out of parental responsibility.

The next major debate took place in early 1881. It revolved round the question of religion. Unfortunately, religion and education had become linked because of the way that society at the time divided. Just as Gilbert and Sullivan would declare that you could be born a liberal or conservative, so equally you could be born church or chapel and, as a generality, if you were church your aspirations were marked out in one way, and chapel in another. Looking back to his Norwich childhood the journalist Massingham would write: “society was divided into two compartments: Church and Chapel…the Established Church founded itself on the old established industries of banking, brewing, wine-selling….” The Dissenters on the other hand “had a hold on the shop-keeping class, and in return for being slightly looked down on in this world, cherished rather confident opinions of its prospects in the next, coupled with serious doubts as to the Anglican position there”[48]. Although tongue in cheek it neatly sums up the difference.

By now the church was defining its position clearly along status of work rather than just creed alone; not that you didn’t have a choice, but somehow few chose to express it. Therefore, education which opened up or closed down opportunities became even more important within this heady mix. So, for example, a son of a shoemaker who was Chapel would be more likely to go to a board school than the Church of England school; and the reverse was true. While the divisions were clear and understood, it could be accepted. But what if, as at Horsham, the Board of Education became dominated by the Chapel? It is easy to see why, although looking back it seems like a minor concern, the debate was so important.